It makes sense for a dissertation writer to start with the literature review; It forces you to think about your topic holistically and understand the context of the area of study you are entering and helps to clarify your thinking about both your question and your methods. But what is it really and how is it judged?

In theory your dissertation is a new and original contribution to scholarly knowledge. That means no one has done it before. In practice, that can be pretty subtle (for example no one has done it for this group before, or using this method, or from this theoretical perspective). Nonetheless you need to place your research in the context of the broader conversation about this topic. Just because no one has done exactly what you have before doesn’t mean that they aren’t talking about it. The literature review is where you do that, and at its most general is just a summary of the conversation to date. However in doctoral education it is never quite that simple.

Finding the literature is often the easy part. In fact, it’s veray easy to find way too much. The big commercial library databases are a good place to start looking, including listings of recent dissertations. (As a side note I am finding that reading a couple of dissertations has helped me to get a handle on the expectations and tone. Even tangentially related dissertations have helped with this.) Once you find a few relevant documents, their bibliographies are the next step in the chain. Many fields prefer you start from great canonical articles. These can be used with a tool like Web of Science to back-track everyone who has cited that article up to the present day and make finding the state of the subject quite easy. A little time with a reference librarian to fine tune your search terms and learn some of these more obscure tools is time well spent.

But it had never been clearly articulated to me what made a literature review good. In reviewing a journal article recently I discovered what made one bad: one paragraph per study, summarizing the population, methods and findings, with no consolidation or theme. In effect it was an annotated bibliography, and it was awful (not to mention painful to read). As my adviser once told me, a literature review should have an argument; a common thread that not only explains what has come before but helps you tell the reader why your work is important and why your conclusions matter.

An article provided by a friend in my reading group has given me a much better understanding of the elements of a good literature review.

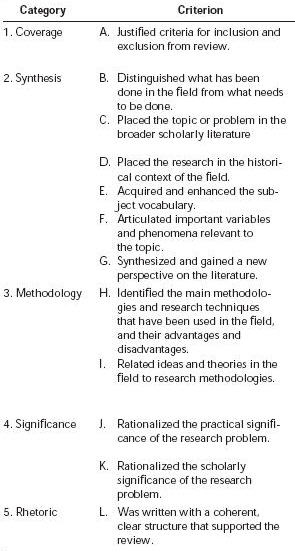

This chart* summarizes what I think are an excellent set of criteria for judging a literature review. It also sets the bar quite high as far as what a student needs to accomplish.

This chart* summarizes what I think are an excellent set of criteria for judging a literature review. It also sets the bar quite high as far as what a student needs to accomplish.

The first item on the list is Coverage, and this requires some explaination. It is very easy to undersearch (not find everything), oversearch (find everything and include it even when it makes no sense, is out of date or repetative), or fail to truly think about why you are including something. The items you include should be purposeful and well thought out; not just there to prove that you’ve read everything regardless. Moreover you MUST keep up with the literature as your research progresses. The lit review is the first chapter you work on, but it should also be the last one you look at before you turn the dissertation in.

Synthesis is the second category and is what seperates a scholar from an undergrad; any undergrad can regurgitate a list of articles, but it takes a more sophisticated approach to look at the broader picture, find the commonalities and differences, and call out the gaps.

Methodology was a new one for me. The authors argue that a good review looks at both the main methodologies used in the area, but also evaluates them, looks for gaps and proposes potential new approaches. In a perfect world the new approach should be precisely what you are doing in your dissertation.

Significance is an interesting one in education. We produce PhDs (thought to be more research oriented) and EdDs (thought to be more practice oriented). Some would argue that this should result in different criteria for the literature review, although the authors of the chart disagree. I would suggest that all doctoral students need to understand both, but that the balance (60% scholarly / 40% practical or vice versa) could change depending on the degree and the topic.

The last category is Rhetoric, which relates back to my adviser’s comments. The quality of the writing needs to be clear, organized and integrated with the rest of the document.

As I am reading, I am trying to keep these ideas in my mind. As I read abstracts I am trying to place the topic within the broader academic conversation, and using that placement to decide whether I am going to read the entire article or skip this. I am using tagging to help with synthesis and methodology, and for now am not eliminating any articles I find. Later I intend to trim and note why, but feel that I need that big picture first. By knowing what a good literature review looks like first I hope to be able to produce one.

* Boote, D. N. P., & Beile, P. L. (2005). Scholars Before Researchers: On the Centrality of the Dissertation Literature Review in Research Preparation. Educational Researcher, 34(6), 3-15.

stumbled onto your website while searching for blogs that mentioned lit reviews. i read the Boote article earlier this semester and it really helped wrap my head around what exactly i need to accomplish in a lit review.

i was reading your old blog posts and am curious to know how did using Dragon NaturallySpeaking in transcribing your thoughts work for you in terms of keeping track of your ideas and thoughts on your readings. i’m looking for a way to better organize all the information i’m coming across in my reading as i tackle my summer reading list.

anyhow- thanks for a great blog!